For the past month I’ve been making sourdough loaves with my starter Dusty1. This has ranged from classic rye loaves, to fully gluten-free loaves using buckwheat. Today I’m sharing the last of this series: experimenting with semolina.

I don’t intend to stop baking, and in fact I’ve just prepped a few ingredients for a savory sourdough loaf that I plan to bake this weekend (really psyched for this one…!). However, I want my next sourdough articles to be focused on either perfected (or near-perfected) recipes, or discussions of thorough experiments that I’ve conducted.

Why Semolina?

I would be very impressed if the first thing that comes to your mind when I say “semolina” is bread. This would indicate that you’ve snapped out of the propaganda pushed by Big Wheat and Big Pasta. Congrats: you’re no longer part of the Carbs Industrial Complex, and you should consider yourself a person with a refined palette.

Jokes aside though: semolina breads that resemble loaves are really rare, mostly because it is really difficult to get semolina to develop gluten networks. It is for this reason that all semolina based breads that I’ve had, with the exception of Italian semolina loaves, have been unleavened flatbreads.

So you might be asking yourself: if people don’t work with this dough, why did I choose to experiment with it? I have two very compelling reasons:

- If you’ve read anything about this blog, then you know that it’s all about self-torture

- Semolina bread makes for the tastiest crusts

Because point 1 is a lie, I didn’t push myself to make a proper leavened loaf. Instead I chose to work semolina into my base rye recipe to see if I can enhance flavour without changing the dough preparation at all2.

The Base Loaf

The base recipe that I used for iterating is a rye loaf from e5 Bakehouse:

- 120 g 100% hydration rye levain (last feed 8-12 hours ago)

- 220 g water

- 55 g wholemeal rye flour

- 180 g light rye flour

- 40 g sunflower seeds

- 40 pumpkin seeds

- 6 salt

Semolina Fed Starter

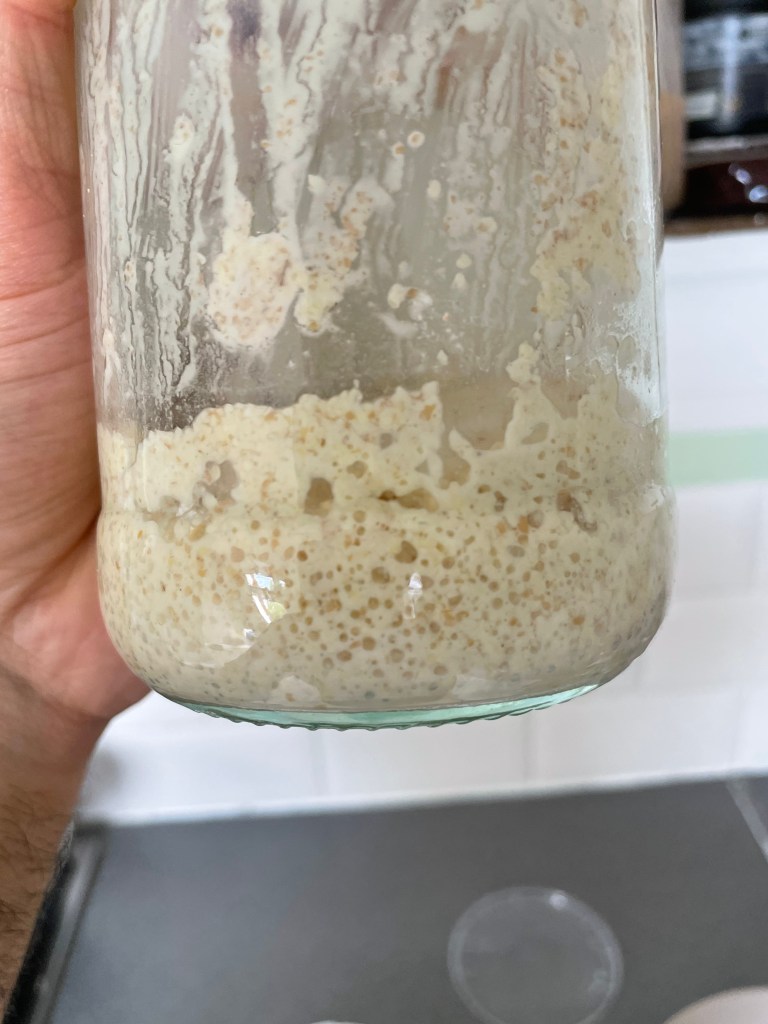

Before adding semolina to my bread, I was curious to see if Dusty can have semolina. She seemed to enjoy it quite a bit, though because semolina is fairly dense, the levain never rose that much. I didn’t run any thorough experiments to measure the effect of using semolina on the bacteria/yeast cultures, but anecdotally I can confirm that the breads that I made with the semolina levain had excellent rise.

Semolina Spelt Loaf

The first experiment I tried was when I was still working with spelt. Here I modified the base recipe to the following:

- 120 g 100% hydration semolina levain (last feed 8-12 hours ago)

- 220 g water

- 180 g semolina flour

- 55 g spelt flour

- 80 g mixed seeds

- 6 salt

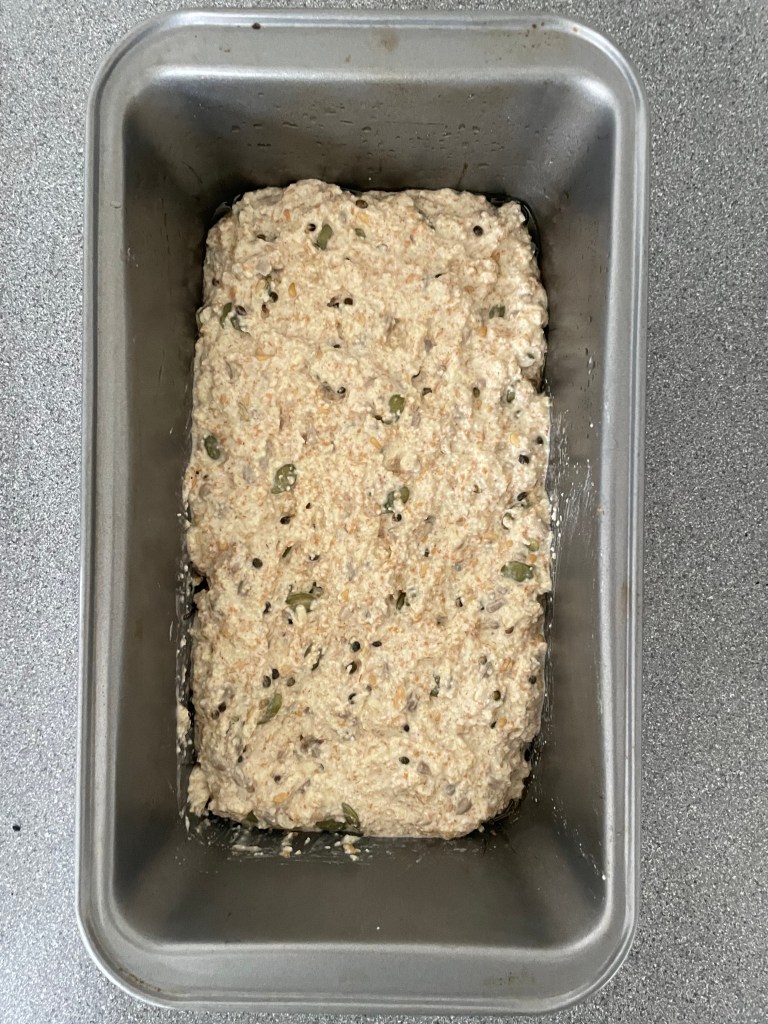

As you can see in the photos below, this turned out super sticky and grainy. Also, the semolina flour I used was not super fine, and consequently I felt like the dough didn’t really absorb much water. You can see that it also didn’t rise that much!

The outcome was a really hard and dense… but believe me when I say it was unbelievably flavorful.

I really enjoyed the flavour. I wish I could explain what it tastes like, but I really can’t think of the words. All I can say is that where rye and spelt shine with the help of salt, semolina lets the salt shine, without making your bread salty. The crust becomes concentrated with flavour, and it develops a proper crunch, deserving of the name “crust”!

As a side note: it worked so well with the mixed seeds, particularly with the sunflower seeds. It was a shame that this first attempt ended up so… tough. I was determined to try this again but with slightly different ratios.

Semolina Rye Loaf

For my second attempt, I decided to switch to rye instead of spelt (mostly because I was having great success with rye, and I’d almost run out of spelt…!).

My recipe for the second attempt was:

- 120 g 100% hydration wholemeal wheat levain (last feed 8-12 hours ago)

- 220 g water

- 150 g semolina flour

- 85 g medium semolina flour

- 6 salt

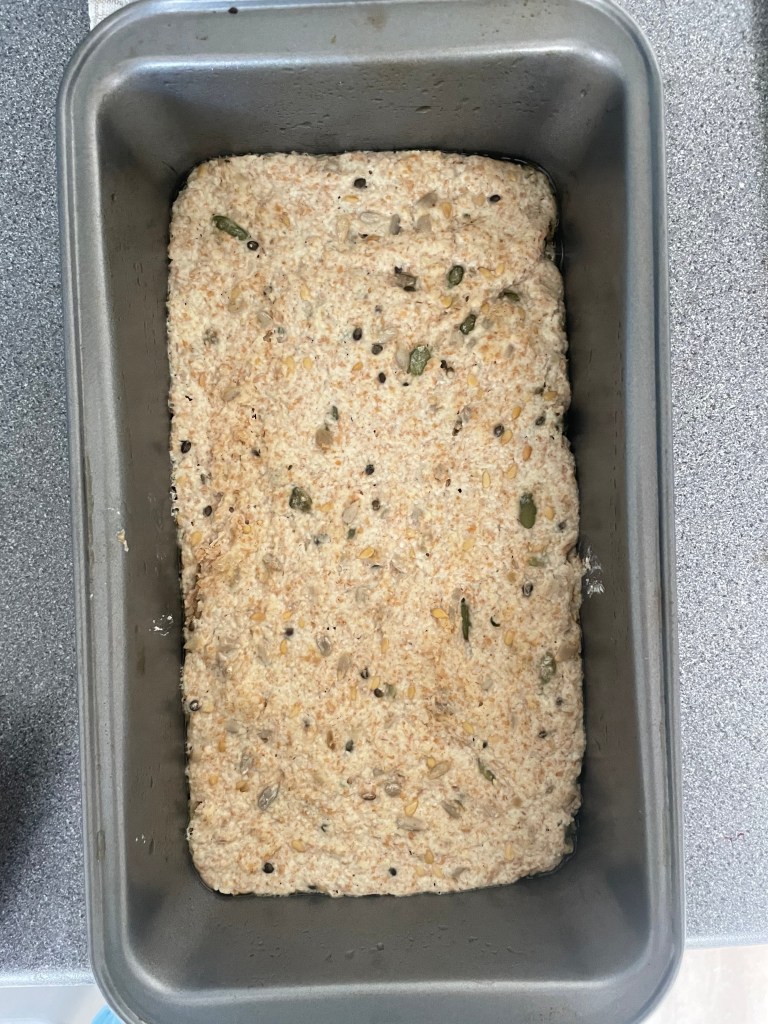

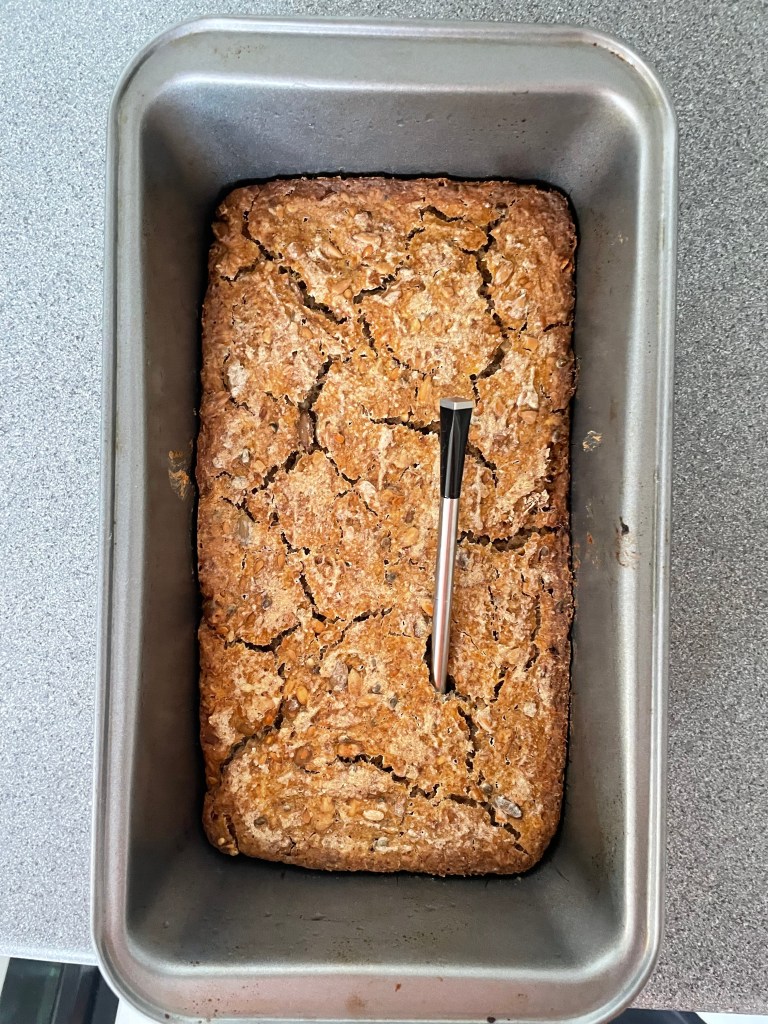

This dough resembled bread more than the previous one. It turned out reasonably soft, with an excellent crust (flavour, crunch and color).

However, this time the dough itself didn’t hold very well, and the bread deformed during the proofing process. Cleaning this was a bit of a pain I’m being honest.

This “separation” of the dough prior to, or during baking, has happened to be before. Previous times I attributed it to the use of moisture holding ingredients, or sugars that really accelerated the rate of fermentation. This time, I think that it might be because of the combination of rye AND semolina: the gluten formation of this combo is very small, and this could explain why the dough didn’t hold it’s shape.

For next time, I would let it rest for longer than 10 minutes before placing it into the tin, to see if the autolyse process will help with gluten formation. Some more manhandling prior to resting might be a good idea too.

I would like to think that the use of finer semolina would have helped, but this needs to be proven through experimentation.

Concluding Remarks

Semolina is an ingredient that I’ll definitely use for baking again, and part of me is tempted to try it in sweet recipes too. For now though… I’m moving onto baking savory loaves… the kinds that would be excellent as appetizers or pairings for rich curries.

As soon as I have some working recipes, I’ll share them!

Leave a comment